Hot Topic Blog - Oral/Pharyngeal Sensory-Motor, Orofacial Myofunctional, & Airway Information

A CASE STUDY - EFFECT OF ORAL SENSORY-MOTOR TREATMENT ON EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE: PART 4By Krupa Venkatraman, Speech-Language Pathologist in IndiaDecember 2017 |

|||

|

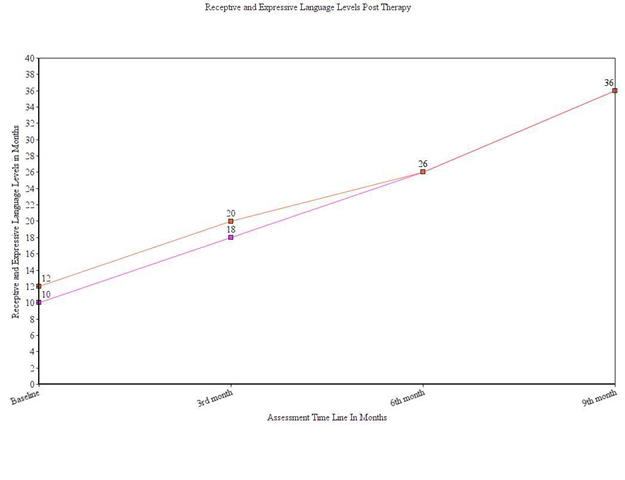

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION The outcomes of the therapy were assessed regarding the overall change in receptive and expressive language levels at three points in time. After the baseline evaluation, three evaluations were done with three-month interval between each (3rd month, 6th month, and 9th month). The client’s language levels were assessed using the Language Acquisition Tool (LAT). The client’s receptive and expressive language levels at three different intervals in the process of treatment are shown in Figure 1. The line graph shows a steady increase both in the receptive and expressive language levels of the client in the subsequent re-evaluations done at three points in time during therapy. Figure1: Receptive and Expressive Language Levels Post Oral Placement Therapy

At the end of the first month, the client could produce labial and labial-dental sounds in combination with vowels in CV and/or VC combinations without support (i.e., “p, b, m, and v”). During the second month of the first quarter, tongue placement for the sounds “t, th, k, g, n, l, and j” along with well-selected and appropriate sensory-motor stimulation began. By the end of the first quarter, the client could name items within different lexical categories such as fruits, animals and their sounds, common objects, birds and their sounds, vehicles, as well as vegetables with minimal support. He could also express family members’ names and functional words by the end of the first quarter. The client’s mean length of utterance was approximately one word per utterance in spontaneous speech without support. His receptive language levels had risen to 18-20 months. His expressive language levels had risen to 16-18 months. During the second quarter, the client was focused on maintaining the achieved oral placements for lingual, labial, and labial-dental sounds. He could also produce the fricatives (“s, sh, and ch) with prompting. The language goals were primitive sentences using S+O, V+O, O+V (i.e., subject plus object, verb plus object, object plus verb). Grammatical expansion using case markers was also facilitated. During the second month of the second quarter, the client could produce three word utterances with minimal prompts. By the end of this quarter, the client could describe action verbs, adjectives, opposites, and prepositions seen in pictures. His receptive language and expressive language levels showed a steady increase to 24-26 months post six months of therapy. By the third quarter, the client could speak in primitive sentences with 3-4 words per utterance. He exhibited slow labored, dysarthric speech. Intelligibility was better when the listener paid specific attention to his speech. After re-evaluation, language goals were changed to simple description and questioning. After nine months of treatment, the client could narrate daily activities with minimal verbal prompts. He was also able to narrate pictures containing three simple sequences (e.g., “What’s next?”). Additionally, the client could express polar questions, as well as “what, who, and where” questions with 70% accuracy. The client was included in a regular school program, and home plans were given to improve his speech clarity and timing. At the end of the third quarter, the client’s receptive and expressive language levels were 33-36 months. While the client has continued to have hemiplegic attacks, his expressive language seems to be adequate. However, his clarity for speech varies with episodes of hemiplegia. When the client recovers from the hemiplegia, his speech clarity is intelligible without needing listener’s complete attention. The client’s expressive language levels seemed to increase post oral sensory-motor and oral placement therapy (OPT). Therefore, oral sensory-motor and OPT seemed to compliment traditional language stimulation techniques. However, during the first eight months of traditional therapy prior to OPT, his comprehension steadily increased, but the few NSOMEs (non-speech oral motor exercises which were not OPT) used during this period did not elevate his expressive language levels. These results are consistent with the concerns about NSOMEs which only activate generalized muscle groups (Lof, 2009). In contrast, specific oral sensory-motor treatment and OPT (which directly address speech oral movements) in combination with neurodevelopmental therapeutic approaches assisted the client in significantly improving his receptive and expressive language. It is, therefore, important to create muscle memory for speech production in those children exhibiting muscle weakness, dysarthria, and dystonia to facilitate language expression. Children with muscle function disorders exhibiting limited vowel and consonant inventories seem to require the use of well-selected and specific oral sensory-motor treatment and OPT. Green, Moore, and Reilly (2002) suggested that oral awareness is the key to aiding spontaneous speech production in children. Similar to jaw grading, children develop the movements of lips and tongue with maturation. Maturation is delayed in clients exhibiting developmental delays. The need for oral sensory-motor treatment and oral placement assistance seems vital in conditions involving muscle function disorders to facilitate sensory-motor learning for speech. Similar techniques are used to teach other fine motor skills (e.g., hand use). CONCLUSION Oral Placement Therapy (OPT) appears to be an update of Van Riper’s PPT (phonological placement therapy, Van Riper, 1978). It is not NSOME. While it may use some traditional oral sensory-motor techniques (Lee and Gibbon, 2011), each technique is used for a particular reason in the development and maturation of speech. OPT facilitates muscle-based speech production. These principles when used in conjunction with NDT and traditional language stimulation techniques can facilitate quick clinical results in terms of verbal output in conditions such as muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, and other movement disorders. REFERENCES Green, J. R., Moore, C. A., & Reilly, K. J. (2002).The sequential development of jaw and lip control for speech. .Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 45(1), 66-79. Lee, A. S. Y., & Gibbon, F. E. (2011). Non‐speech oral motor treatment for developmental speech sound disorders in children. The Cochrane Library. Lof. G. L. (2009, November). Nonspeech oral motor exercises: An update on the controversy. Session presented at the annual meeting of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, New Orleans, LA. Van Riper, C. (1978). Speech correction: Principles and methods (6thed.) Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Krupa’s Career: I started my career in 2011 and worked at a few child developmental centers and special schools. However, I was determined to start my private practice where I am free to employ my way of looking at a disorder or a condition. I happened to work with the pediatric population, predominantly children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Cerebral palsy, ADHD etc. I do on-call visits to hospitals for bedside evaluations of adults with neurogenic communication disorders, addressing feeding, oral sensory-motor issues, and communication. I received my undergraduate and post-graduate education at Sri Ramachandra University, Porur, Chennai, India. I was awarded a gold medal for academic and clinical performance. I like to work with a variety of disorders; however, oral sensory-motor programs are my prime area of interest. You may contact me via email: krupa1288@gmail.com. |

|||