Hot Topic Blog - Feeding, Eating, & Drinking

A TRANSITIONAL SNACK FOR THE PEDIATRIC POPULATION: THE EAT BARBy Tia Bagan, MS, CCC-SLP, Co-Founder of Nutraphagia, from Chicago, IL, USAMay 2019 |

|||

|

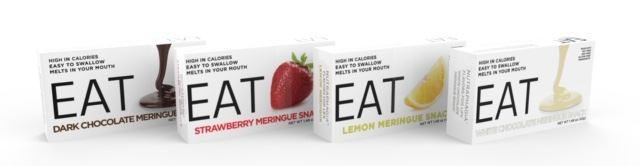

As a parent or caregiver, we often use a combination of acquired information and intuition to help guide us as we transition a child from pureed foods to solid foods. When we finally begin feeding our child with small spoonfuls of perfectly blended smooth textures, we also notice signs indicating a child’s desire or readiness to move onto another consistency. There may be clear indicators of precursors for mature chewing (e.g., tongue lateralization and diagonal rotary chewing) beginning around 5 to 6 months of age (Morris & Klein, 2000; Morris, 2003). As these early eating skills develop, there may be fear around feeding because of the increased risk of a child coughing and/or choking on solid foods. So, parents might try to reduce this risk by presenting a dissolvable or melt-away solid food that softens with saliva. These foods promote texture change, taste experience, oral sensation, chewing, and the development of oral sensory-motor skills. Finger foods may also encourage self-feeding, as well as help with hand-eye coordination, visual perceptual skills, and overall neural integration. What Are Transitional Foods? In 2013, a group of volunteers from various professions around the world gathered to standardize how we define foods and liquids. They established transitional food textures as those that start as one texture (e.g., firm solid) and change into another texture specifically when moisture (e.g., water or saliva) is applied. This food texture is used in developmental teaching or rehabilitation of chewing skills. For example, it is used in the development of chewing in the pediatric population and developmentally disabled population. (Gisel, 1991; Phalen, 2013; IDDSI.ORG) Disordered Feeding Feeding difficulties may be identified as children are advancing through different stages or phases of feeding. Parents can track their child’s feeding development via resources such as those written by Bahr (2010, 2018) which have specific criterion-referenced, literature-based, parent-friendly feeding checklists and instructions. Refusal to eat, preferences for certain food textures, problems chewing, and not gaining weight all play a role in a child’s overall relationship with food. Causes of pediatric dysphagia may include complex medical conditions, developmental disabilities, sensory-motor issues, and structural abnormalities just to name a few. Ultimately, caregivers are responsible for what, when, and where a child eats. Children, in turn, are responsible for how much and whether they eat. (Phalen, 2013; Satter, 1987, 2000). The Genesis of the EAT Bar: A New Finger Food As a speech-language pathologist, I watched countless patients and their families struggle to find foods that not only fed their bodies but also their spirits. Through my years of clinical practice, I began to recognize the need for a snack that provided easy calories and required limited mastication or chewing. The EAT Bar was developed with the goal of providing individuals a delicious kosher transitional food devoid of genetically modified organisms, gluten, and nuts. Pediatric Case Study A pediatric feeding team sat down with a 4-year-old girl and her mother. The child was a picky eater who consumed mostly pureed foods with occasional solid foods. Her mother had tried to force feed some solid foods which resulted in avoidance. She was concerned as her daughter’s weight had fallen into the 30th percentile from the 40th percentile in a few months. When given a choice of flavors, the child picked a strawberry EAT Bar. It was easy for her to hold and bring to her mouth. She commented positively on its taste and consumed the entire bar. The pediatric feeding team also had other fun recommendations for the use of the EAT Bar: -Structure a tea party with an EAT Bar away from the dining table. This provided a new situation using little cups and plates. -Include a friend or another family member in a treasure hunt (similar to an Easter egg hunt) with the EAT Bar as the treasure. -Offer the EAT Bar when riding in the car if the parent considers it safe. It may not be as easily abandoned as other snacks. Feedback from the Pediatric Communities Since launching the EAT Bar, we have been overwhelmed with the outpouring of support and humbled by all of the inspirational stories we have received. For example, a speech-language pathologist told us the EAT Bar was the first solid food a young boy in her feeding clinic had ever been able to tolerate. A mother discovered her 12-year-old daughter with cystic fibrosis who was gastrostomy tube dependent with a limited appetite loved the EAT Bar. And, a father had twin sons who both loved the EAT Bar, one of whom was a picky eater with food texture issues. The EAT Bar in Adult Populations The EAT Bar is also very useful in adults with stroke, traumatic brain injury, and other disorders where they need to get back to eating. But, this is a topic for another blog. About the Author Tia Bagan is a speech-language pathologist and co-founder of Nutraphagia, a health and wellness company whose mission is to bring joy, delight, and care to everyone every day and the creator of the EAT Bar. She completed her undergraduate training at the University of Iowa’s Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders. She continued her graduate training at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois, and was fellowship-trained at John Stroger Hospital of Cook County. She returned to Rush University Medical Center as a Clinical Supervisor and Lecturer for 5 years. Throughout her 15-years of practice, Tia has provided patient care in the acute care hospital, out-patient, rehabilitation, skilled, and long-term care facilities. Through independent research of dysphagia products over the years, she saw a discrepancy between the needs of her patients and food offerings on the market. Tia is also a member of the American, Language, Speech and Hearing Association and has received the ACE award for excellence in continuing education. Contact Tia via www.theeatbar.com. References Bahr, D. (2018). Feed your baby and toddler right: Early eating and drinking skills encourage the best development. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons/Sensory World. Bahr, D. (2010). Nobody ever told me (or my mother) that! Everything from bottles and breathing to healthy speech development. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons/Sensory World. Gisel, E. G. (1991). Effect of food texture on the development of chewing of children between six months and two years of age. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 33(1), 69-79. International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative. Retrieved from http://www.iddsi.org on April 19, 2019. Morris, S. E. (1978, revised 2003). A longitudinal study of feeding and pre-speech from birth to three years. Unpublished research study. Faber, VA: New Visions. Morris, S. E., & Klein, M. D. (2000). Pre-Feeding skills: A comprehensive resource for mealtime development (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: PRO-ED, Inc. Phalen, J. A. (2013). Managing feeding problems and feeding disorders. Pediatrics in review, 34(12), 549-557. Satter, E. (1987). How to get your kid to eat…But not too much. Boulder, CO: Bull Publishing. Satter, E. (2000). Child of mine: Feeding with love and good sense. Boulder, CO: Bull Publishing. |

|||

Transitional Foods Are Part of Normal Development

Transitional Foods Are Part of Normal Development